My Son👦, Solved

Owen Cain is six. He can't move or speak. For years, Hamilton wasn't sure he understood anything he told him. Then one day, he started writing.

By Hamilton Cain

I've just spent the afternoon running errands around town. As I turn the key in my front door, I listen for signs that my son Owen may be in trouble. But today I hear only the blessed whoosh-whoosh of Owen's ventilator as it pumps air in and out of his lungs. I glance at him through his bedroom door: he's reclined on a foam pillow, napping. His heart rate is normal, his oxygen saturation in the high nineties. Perfect. His day nurse, Robyn, is jotting notes in his chart. She looks up and hands me a note.

Daddy: you are so very great. Your family loves you so much for doing family stuff always. I love your you. Your son, Super Owie.

An ache stings at the back of my throat. I swallow a sob. Although he's six years, Owen has never spoken a word. His disease paralyses him- he can barely move his arms and legs, much less his lips. I'd long ago written off the idea that we would ever communicate.

Then, last summer, we put a pen in his hand.

When Owen was born, he went into respiratory distress and spent 7 months in intensive care. He was suffering from spinal muscular atrophy, a disease in which the signals between the spinal cord and muscles are weak or, in severe cases, nonexistent. Although his health improved, my wife and I confronted the fact that he'd remain mostly in bed, immobile, for the rest of his life.

Beneath the straightjacket of his disease, a primal instinct flickered: he began to vocalise a few rudimentary consonants, "g" and "k" and "s". After his discharge home, though he fell silent as he grew older, he found his own ways to convey discomfort, annoyance or pleasure. As he approached pre-primary age, we enlisted a team of therapists to help him, but saw limited results. The speech therapist seemed especially concerned. "There's a window of time for him to acquire words," she said. "I'm just afraid that window's closing."

Late one spring evening not long after Owen's fifth birthday, we watched a documentary about NASA's mission to Saturn. As Owen sprawled on his left side, propped by the pillows, I noticed him staring fiercely at the screen, soaking in the details. Now, the narrator intoned, Voyager 1 is the furthest human made object from the sun, more than 16 billion kilometres away, racing at the speed of 17km per second. Mountains will crumble to dust, continents will merge and break away, the sun will wink out and still Voyager 1 will continue on its airless curve for billion of years, shooting away. Forever.

I felt dizzy and needed something to ground me in the here and now. I switched off the television and played a song at low volume, dancing Owen's hand to "My Flying Saucer", a Woody Guthrie lyric set.

My flying saucer, where can you be

Since that sad night that you sailed away from me?

My flying saucer, I pray this night

You will sail back before the day gets bright...

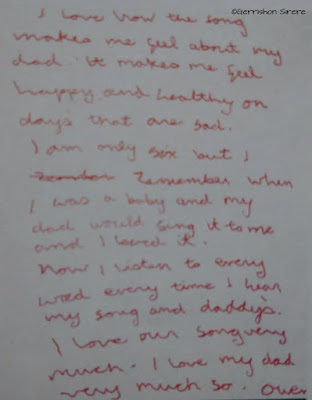

One month later, Owen's occupational therapist figured out that if she gripped his wrist at a particular angle, he could wield a felt-tip pen. As summer turned to winter and then spring, Owen's spare letters evolved into a fluent script, each entry brimming with distinct idioms. Mom, I love your you. (We believe he means "your essence") Sometimes he'd embellish a note with cartoons: a ripple of clouds, a scrawled daisy, an inverted Pacman that he claims is his symbol for laughter.

Today, he writes a request : Would Robyn read aloud a book about space? She kneels and fans four books across the parquet floor.

I lean against the doorway, lulled by Robyn's serene delivery. A quiet exhilaration pulses through me: my boy, his curiosity bursting through the cage of his body to touch the vault of the universe. After she's done, in a surge of bravado, he asks for a test. Robyn sifts through his space books, scribbling questions on a tablet. She tells him the test will be difficult.

I linger in the doorway again until she brings the completed test for my review. He's scored a perfect hundred, my little boy with the twisted body and limpid eyes, determined to make his mark in the solitude of his room.

My flying saucer, fly back for home! You'll get lost in the universe alone!

I kneel beside Owen and squeeze his hand, a communication that transcends mere words. From this moment forward, we will carry on the most intimate of conversations, our sentences woven into a tapestry as sumptuous as a night sky. It's the story of parent and child. And finally, we'll be able to write it together.

©Gerrishon Sirere

0 comments

Thank you for your comment. You're much appreciated.

Take care Xx❤!